Buckminster Fuller, The World Game, and Livingry

A Blueprint for a Thriving Humanity

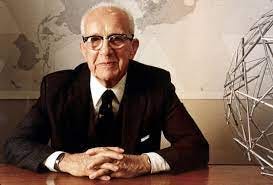

The Visionary Legacy of Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) was an American architect, engineer, systems theorist, and futurist whose work defied categorization. He was neither a traditional scientist nor a conventional designer; instead, he operated at the intersection of multiple disciplines, pursuing what he called comprehensive anticipatory design science. His life's mission was to create tools, concepts, and systems that could help humanity transcend scarcity, achieve planetary prosperity, and unlock the potential for a regenerative civilization.

At the core of Fuller's philosophy was the idea of livingry, a term he coined to describe inventions and technologies that enhance life rather than destroy it. In contrast to weaponry, which diverts resources toward war, and killingry, which is used to dominate and oppress, livingry is about designing systems that ensure the well-being of all people while operating within the regenerative cycles of nature.

One of Fuller's most radical proposals for achieving global abundance was The World Game—a planetary-scale simulation that encouraged people to think systemically about Earth's resources, population, and human needs. The World Game was his answer to the zero-sum mindset of geopolitics, replacing conflict-driven competition with a collaborative approach to solving humanity’s greatest challenges.

This essay explores Fuller’s vision of livingry, the mechanisms of The World Game, and how these concepts can be applied today to create a world that works for everyone.

The Maverick System Thinker

Fuller’s personal and professional journey was shaped by his commitment to what he called “doing more with less.” Early in his life, he experienced a period of deep personal crisis and even contemplated suicide. However, he decided to devote himself entirely to an experiment: to determine whether one individual could make a meaningful difference in improving the lives of all humanity. He committed to thinking in terms of the “biggest possible picture” and using the scientific method not to exploit but to elevate civilization.

His approach to design was rooted in nature's principles. He studied how energy and matter organize themselves efficiently in natural systems—whether in the structure of atoms, the geodesic strength of a honeycomb, or the dynamics of ecosystems. This led him to design breakthrough innovations such as:

The Geodesic Dome: A lightweight, self-supporting structure that became one of the most efficient architectural designs ever conceived.

The Dymaxion Car: A fuel-efficient, aerodynamic vehicle decades ahead of its time.

The Dymaxion House: A modular, sustainable housing prototype designed for affordability and self-sufficiency.

Synergetics: A framework for understanding reality based on geometric patterns found in nature.

Fuller was not just designing objects; he was designing a new way of thinking—one that emphasized the interconnectedness of all things. His work anticipated modern ecological and sustainability movements, and his insights remain profoundly relevant in an age of climate crisis, economic disparity, and technological disruption.

The World Game:

Replacing Scarcity with Synergy

One of Fuller’s most profound contributions was The World Game, an alternative to war games played by governments and military strategists. Traditional war games assume a zero-sum model, where nations or factions compete for resources, dominance, or control. In contrast, The World Game asks a fundamental question:

How do we make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time, through spontaneous cooperation, without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone?

A. The Mechanics of The World Game

The World Game was originally played in large-scale participatory settings, where teams of players acted as global problem-solvers. Using comprehensive data about Earth's resources, technological capacities, and social needs, players sought to model and implement solutions that could eliminate hunger, poverty, and energy crises.

Participants had access to real-world information about:

Global energy production and consumption.

Food distribution patterns.

Economic and political systems.

Environmental sustainability.

Population growth and demographic trends.

The game’s goal was to identify synergetic solutions—those that increase overall human well-being without requiring sacrifice or harm to others. Players were encouraged to explore emergent strategies such as:

Renewable energy systems to replace fossil fuels.

Circular economies to eliminate waste.

Decentralized, localized production networks to reduce dependence on global supply chains.

Open-source knowledge-sharing to accelerate innovation.

Unlike traditional games, which have winners and losers, The World Game aimed for an “all-win” scenario—one where every individual, community, and nation benefits from smarter design and better resource allocation.

B. The World Game as a Tool for Systems Thinking

What made The World Game revolutionary was its approach to comprehensive thinking. Fuller believed that partial, fragmented solutions—those that only address symptoms rather than root causes—would never solve humanity's grand challenges. Instead, he proposed that we must think holistically, seeing the entire planet as an integrated system.

This philosophy is echoed in modern fields such as:

Systems dynamics (used by MIT’s Jay Forrester in modeling complex interactions in economies and ecosystems).

Circular economics (as proposed by Ellen MacArthur Foundation).

Regenerative design (championed by architects and urban planners to create self-sustaining environments).

Today, The World Game could be revived in a digital format, leveraging artificial intelligence, big data, and blockchain to simulate global-scale decision-making. By integrating real-time data into a planetary dashboard, we could create a participatory platform where millions collaborate to build a thriving future.

Livingry:

Engineering a Post-Scarcity Civilization

Fuller’s ultimate goal was not just to think about better systems but to build them. He saw The World Game as a stepping stone to an era where humans move beyond survival mode and into a world of regenerative prosperity. This is where livingry comes into play.

A. The Definition of Livingry

In Critical Path, one of Fuller’s most influential books, he defined livingry as:

"The opposite of weaponry and killingry—designs and artifacts that enhance human life, increase efficiency, and ensure sustainability."

Livingry includes:

Renewable energy technologies that free humanity from dependency on fossil fuels.

Affordable housing solutions that are self-sustaining and climate-adaptive.

Autonomous food production systems that eliminate hunger.

Open-source medical innovations that provide universal healthcare.

Decentralized, self-organizing economies that allow communities to thrive without centralized control.

Fuller believed that livingry was not just a technological challenge but a moral imperative. If we have the capacity to design systems that make life easier, safer, and more meaningful, then it is our responsibility to implement them.

B. Doing More with Less: Ephemeralization

One of Fuller's key principles was ephemeralization—the idea that technology enables us to do "more and more with less and less until we can do everything with nothing." This can be seen in:

The miniaturization of computing power (from room-sized machines to smartphones).

The efficiency of solar and wind energy compared to coal.

The rise of 3D printing and decentralized manufacturing.

In Fuller’s vision, ephemeralization would eventually lead to post-scarcity—a world where all basic human needs are met without destructive competition for resources.

Applying Buckminster Fuller's Vision Today

Fuller’s work is more relevant now than ever. As humanity faces climate change, social inequity, and technological upheaval, his principles offer a roadmap for creating a world that works for all.

Global Resource Optimization

The World Game could be resurrected as a real-time planetary simulation, using AI to model the best ways to allocate resources.

Circular and Regenerative Design

Instead of linear economies (which create waste), we can implement closed-loop systems that continuously reuse materials.

Decentralized, Networked Economies

Fuller's vision aligns with blockchain and Web3 principles, where value creation is distributed, and individuals have more control over their resources.

New Forms of Governance

Moving beyond nation-states, we could develop planetary cooperation networks that focus on synergetic solutions rather than competition.

The Buckminster Fuller Challenge for the 21st Century

Fuller believed that humanity was at a critical juncture: We could either continue our path toward destruction or embrace comprehensive design science to create a world of abundance. His legacy is not just about domes or technology—it is about a fundamental shift in how we think about human potential.

If we resurrect The World Game, invest in livingry, and embrace ephemeralization, we can bring Fuller’s vision into reality. The question is not whether this is possible—the question is whether we have the will to make it happen.

"We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims." — Buckminster Fuller